One of the landmarks of Progressive Era legislation was the White Slave Traffic Act — better known as the Mann Act for its author, Illinois congressman James Robert Mann. The Mann Act made it a crime to transport women across state lines "for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose." While designed to combat forced prostitution, the law was so broadly worded that courts held it to criminalize many forms of consensual sexual activity, and it was soon being used as a tool for political persecution of Jack Johnson and others, as well as a tool for blackmail.

The Mann Act was born during the "white slavery" hysteria of the early 20th century. Along with other moral purity movements of the period, the white slavery craze had its roots in fears over the rapid changes that the Industrial Revolution had brought to American society: urbanization, immigration, the changing role of women, and evolving social mores. As young, single women moved to the city and entered the workforce they were no longer protected by the traditional family-centered system of courtship, and were subjected to what Jane Addams called the "grosser temptations which now beset the young people who are living in its tenement houses and working in its factories."

As Progressive Era social reformers (many of whom did not distinguish between sexually active women and prostitutes) began to call attention to what they saw as a widespread decline in morality, foreigners emerged as an easy target. Unfettered immigration provided an endless supply of both foreign prostitutes and foreign men who lured American girls into immorality. Muckraking journalists fueled the hysteria with sensationalized stories of innocent girls kidnapped off the streets by foreigners, drugged, smuggled across the country, and forced to work in brothels. Borrowing a term from the 19th-century labor movement, muckraker George Kibbe Turner called prostitution "white slavery," and in a 1907 article in McClure's Magazine claimed that a "loosely organized association. largely composed of Russian Jews" was the primary source of supply for Chicago brothels. Pulp fiction and movies (then a novelty) fanned the flames even more.

Politicians seized upon the "crisis" for political gain. Edwin W. Sims, the U.S. district attorney in Chicago, claimed to have proof of a nationwide white slavery ring:

"The legal evidence thus far collected establishes with complete moral certainty these awful facts: that the white slave traffic is a system operated by a syndicate which has its ramifications from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific Ocean, with 'clearinghouses' or 'distribution centers' in nearly all of the larger cities; that in this ghastly traffic the buying price of a young girl is from $15 up and that the selling price is from $200 to $600. This syndicate is a definite organization sending its hunters regularly to scour France, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Canada for victims. The man at the head of this unthinkable enterprise is known among his hunters as 'the Big Chief."

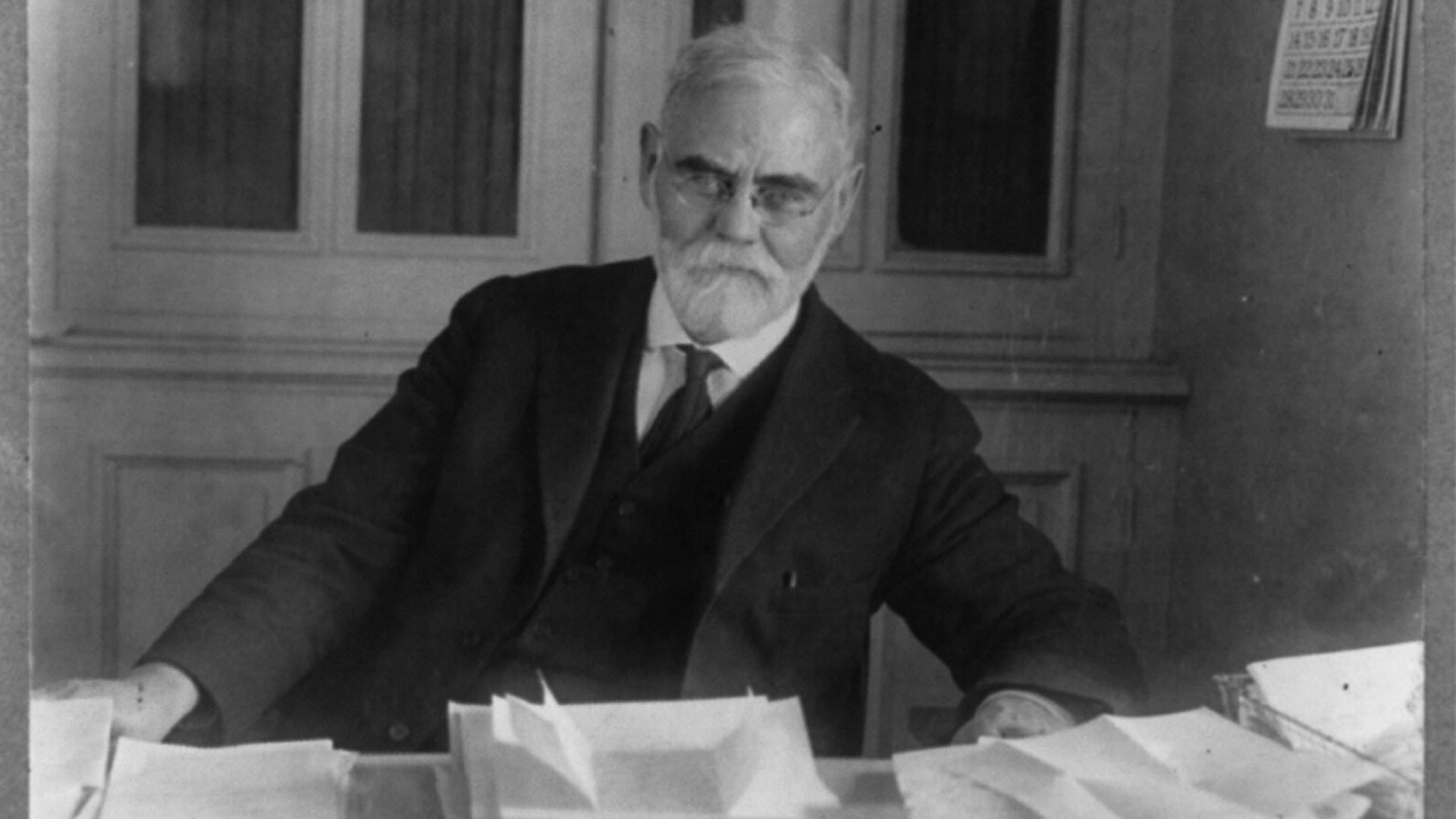

Sims was never able to produce his "evidence," but his friend James Robert Mann, chairman of the powerful House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, quickly drafted a bill to show the public that Congress was doing something about the "crisis." It was also intended to bring the United States into compliance with a 1904 international treaty on forced prostitution, but much of the wording was drawn from a section of the 1907 Immigration Act, which banned the "importation into the United States of any alien woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution, or for any other immoral purpose." Introduced in Congress in June 1909, the bill was quickly passed with little opposition and President William Howard Taft signed it into law later that same month.

While intended as a specific response to commercialized vice, the ambiguity of the "or for any other immoral purpose" clause of the Mann Act (and the similarly worded 1907 Immigration Act), and the fact that the Justice Department's new Bureau of Investigation (now the Federal Bureau of Investigation) was simply unable to find evidence of a widespread "white slavery" network, led prosecutors to begin using it against other forms of sexual conduct.

The Supreme Court repeatedly held these prosecutions to be constitutional. In United States v. Bitty (1911), the Court ruled that the 1907 Immigration Act applied in the case of a man, John Bitty, who had brought his English mistress into the United States. Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote in the opinion that "the words, 'or for any other immoral purpose,' after the word 'prostitution,' must have been made for some practical object. Those added words show beyond question that Congress had in view the protection of society against another class of alien woman other than those who might be brought here merely for purposes of 'prostitution.'"

Two years later, in Hoke v. United States, the Supreme Court held that the Mann Act did not unconstitutionally limit the right of free travel. In Wilson v. United States (1914), the Court declared that travel across state lines with the intention to commit an immoral act was grounds for conviction, even if the immoral act was not executed.

The Supreme Court dramatically widened the scope of the Mann Act three years later in Caminetti v. United States. In March of 1913 Drew Caminetti, the son of a prominent California politician, and a friend, Maury Diggs, both married and having affairs, took their mistresses by train from Sacramento to Reno. Their betrayed wives tipped off the police, and both men were arrested upon their arrival in Reno. Caminetti and Diggs were tried and found guilty. On appeal, Caminetti's lawyer argued that the intent of Congress was to target only "commercialized vice," and that while his client's behavior may have been immoral, it was "free from commercialism and coercion." Citing Bitty, Justice William R. Day wrote for the majority that the language of the Act "being plain. is the sole evidence of the ultimate legislative intent" and that not applying the law in this case "would shock the common understanding of what constitutes an immoral purpose."

Such an interpretation of the law in effect criminalized all premarital or extramarital sexual relationships that involved interstate travel. With behavior that was so commonplace now illegal, federal prosecutors had a weapon that could very easily be abused in order to prosecute "undesirables" who were otherwise law-abiding citizens. Jack Johnson's conviction in 1913 was ostensibly for transporting a white prostitute from Pittsburgh to Chicago, but was motivated by public outrage over his marriages to white women. In 1944, actor Charlie Chaplin was acquitted of a Mann Act indictment stemming from a paternity suit. In actuality, the case was motivated by Chaplin's left-of-center political views and was personally instigated by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who had called Chaplin one of Hollywood's "parlor Bolsheviki." In 1959, black rock 'n roll star Chuck Berry was convicted of violating the Mann Act and served 20 months in prison for transporting across state lines an underage Apache girl who was weeks later arrested on a prostitution charge.

The Mann Act has never been repealed, but it has been substantially amended in recent years. In 1978, Congress updated the definition of "transportation" in the act, and added protection for minors of either sex against commercial sexual exploitation. A 1986 amendment further protected minors and added protection for adult males, and replaced "debauchery" and "any other immoral purpose" with "any sexual activity for which any person can be charged with a criminal offense."